New treatment for most aggressive brain cancer may help patients live longer

A new therapy for the most aggressive type of brain cancer can extend patients’ survival while cutting the length of treatment.

The cancer, glioblastoma, is fast-moving and incurable. It’s most common in older adults, said Dr. Sujay Vora, a radiation oncologist at the Mayo Clinic, and the median survival time for people diagnosed over age 65 is between six and nine months.

“We’re starting to see more and more cases of it as our adult population ages,” Vora told Live Science. The disease killed Sen. John McCain in 2018.

One reason the disease is difficult to treat is, by the time it starts causing symptoms, the cancer is usually embedded in the brain by meandering tentacles of malignant tissue. These tendrils are hard to remove while sparing healthy brain tissue, and the tumors often grow back within months of surgery due to cancerous tissue being left behind, Vora said.

Related: The 10 deadliest cancers, and why there’s no cure

In a recent clinical trial, Vora and his colleagues focused on improving postsurgical chemotherapy and radiation for glioblastoma patients. They wanted to tweak the radiation treatment to both better target the active areas of the tumor and reduce side effects for patients, which can include fatigue and cognitive impairment. Glioblastoma is typically treated with photon radiation, which uses high-energy X-rays to destroy the DNA in cancer cells, thus killing them.

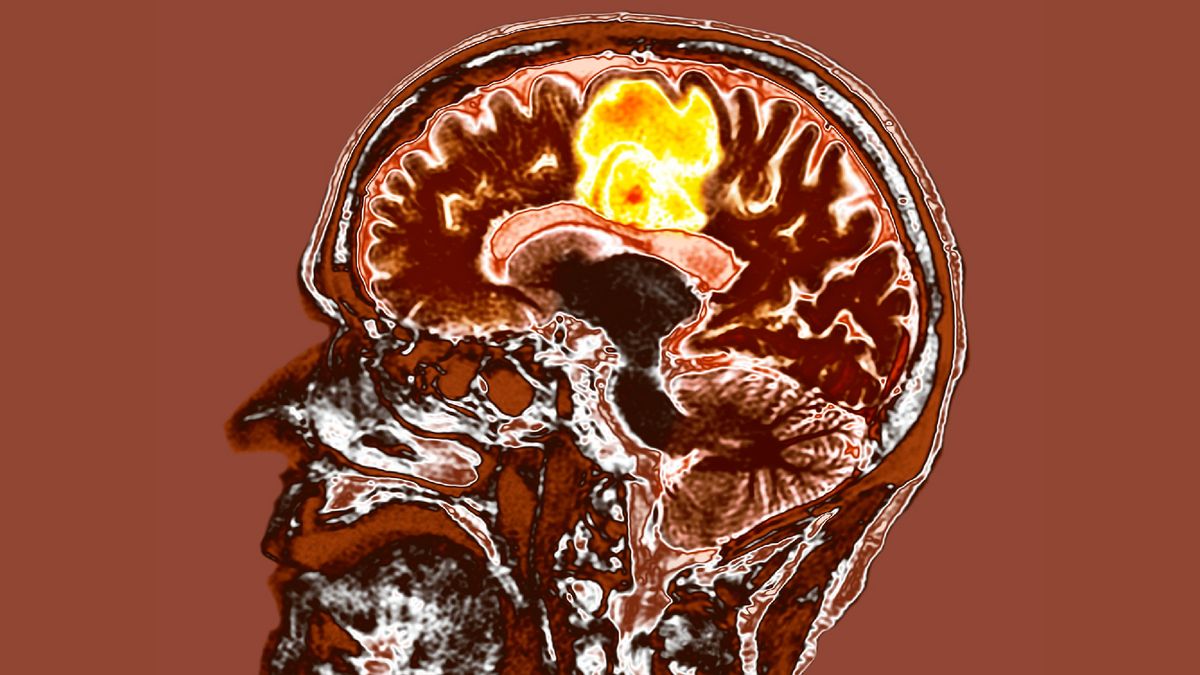

Usually, patients’ tumors are mapped out by MRI before the patients undergo radiation. In the new trial, the researchers added another type of imaging, called 18F-DOPA PET. It’s a kind of positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, a technique in which doctors inject a small amount of radioactive tracer into the patient and the scan then pinpoints where most of that tracer goes. This picks up areas of unusual metabolism — including cancer cells, which are more metabolically busy than healthy cells. 18F-DOPA PET uses a radioactive tracer that is particularly adept at picking up abnormalities in certain neurons.

After the brain scans, the researchers targeted the active cancer regions with a type of radiation known as proton beam therapy. Proton radiation therapy uses charged heavy particles to do the job, rather than the X-rays used in photon radiation.

It’s a more targeted method that prevents damage around the treated area, Vora said. “It basically gives a lot less collateral radiation.”

After undergoing surgery, 39 trial participants received this tumor mapping and treatment for one to two weeks; all of the patients were over 65. Despite the typical survival time for the diagnosis being less than a year, 22 of the 39 patients were alive 12 months after the treatment. And instead of a median survival of six to nine months, the patients averaged 13.1 months.

“It’s really promising data,” Vora said. In some patients with a type of glioblastoma that is less resistant to treatment due to its genetics, the survival time exceeded two years.

Beyond the extended survival time, the brevity of the treatment is also important, Vora noted, because patients often have to travel long distances and stay in temporary housing to get these therapies.

“This is a very difficult diagnosis for patients and families, of course,” he said. “Anything we can do to help with the impact of having to go to the doctor over a long period of time — anything we can do to help reduce that burden, is a good thing.”

The researchers reported their results in December in the journal The Lancet Oncology. The findings were so promising that the Mayo Clinic is now opening up the trial to glioblastoma patients of all ages. The researchers are also comparing the short course of treatment with traditional, three-to-six week treatments, to see if there’s any difference in efficacy.

Elsewhere, researchers are tackling glioblastoma from other angles. For instance, a new treatment being tested in the United Kingdom involves using a medical device to deliver doses of a radiation drug directly into patients’ brains after surgery. And recent clinical trials that use customized immune cells to attack glioblastoma tumors are also showing promise in treating the exceptionally deadly cancer.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

link